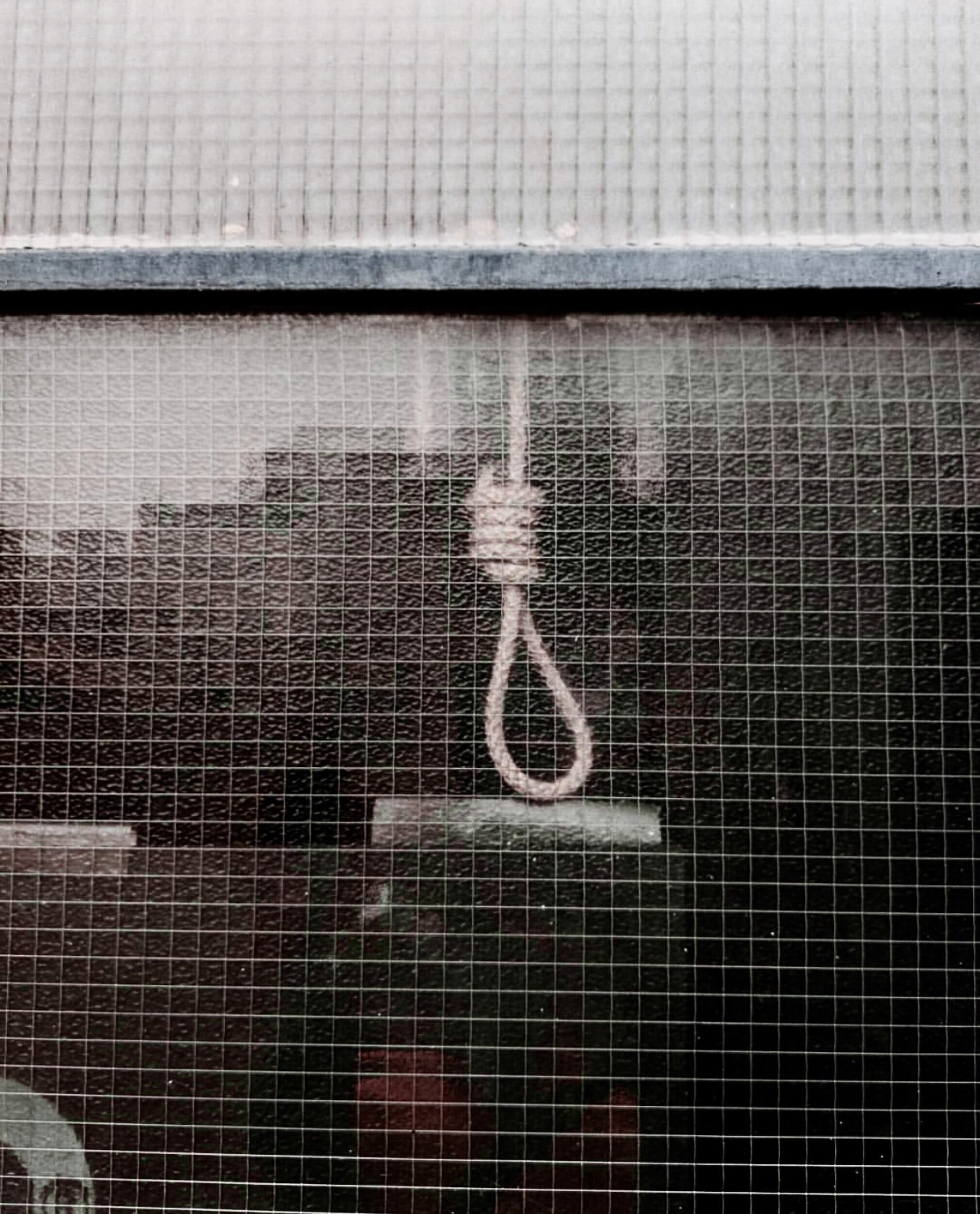

Libya: Penalties up to death against freedom of expression and association

Articles 206, 207, and 208 of the Penal Code are oppressive, unconstitutional, and lack legitimacy in application, violating higher international agreements, according to the Libyan Supreme Court ruling no. 1/57, issued on 23 December 2013.

Law 80 of 1975 amended the three articles during Gaddafi’s rule to punish anyone who opposes the ruling regime through the peaceful exercise of freedom of expression and association, with penalties up to death. These articles further contradict the Libyan Constitution, as Article 14 guarantees freedom of expression, Article 15 freedom of association, and the principle of criminal legality in Article 31. The legal texts of criminalization must be clear, not broad to suit the principle of no punishment and no crime without a legal text. The Supreme Court of Libya established this principle, and confirmed it in ruling no. 1/57 issued in the Abu Salim case on 23 December 2013, stipulating the supremacy of international agreements ratified by the Libyan state. These articles and laws blatantly contradict Article 15, regarding the principle of criminal legality, and Article 19 guaranteeing freedom of expression, and Article 22 the protection of freedom of expression.

Thus, Adala for All Association (AFA) demands:

Members of the prosecution, judges, and the executive authority commit to applying the principles of the Supreme Court with regard to the principle of supremacy, according to the aforementioned ruling no. 1/57 issued in the Abu Salim case, and refrain from applying the three articles until the constitutionality and legality of the three articles are decided by the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court.

A recommendation to any interested party or physical or legal person against whom the authorities attempt to implement any of the three articles. These articles must be challenged for unconstitutionality before the court, and the judge must directly apply the guarantees of the Constitutional Declaration and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in Libya.

The continuity of articles 206, 207, and 208 of the Libyan Penal Code represents the legislative framework that the Gaddafi regime used to eliminate basic freedoms and silence voices. Article 206 stipulates the death penalty for anyone calling for the establishment of any gathering, association, or formation prohibited by law, or for establishing, organizing, managing, financing , or preparing a place for its meetings, and anyone joining or inciting these acts by any means, or providing any assistance. For anyone who receives or obtains, directly or indirectly, by any means, money or benefits of any kind, from any person or from any party, with the intention of establishing a prohibited assembly, association, or formation, or preparing for its establishment, the punishment shall be equal for the leader and the subordinate, no matter how low the rank in the assembly, organization, or formation, and whether this group’s headquarters is inside or outside the country.

The three articles include broad and inaccurate phrases despite the seriousness and severity of the penalties. However, the legislator did not neglect that, and rather intended to employ these texts to expand the scope of criminalization to a degree that affects the principle of the legitimacy of crimes and punishments and the presumption of knowledge of the law, as well as the incompatibility of all actions. The criminal is subjected to the prescribed penalties, whether death penalty, life imprisonment, or imprisonment for the crimes stipulated in Article 208. These texts criminalize the crime in an extensive manner and determine the maximum penalties without any regard to the circumstances of the crime and the extent of the seriousness of each actor’s contribution. Thus, encouraging those who originally carried out criminal acts that could be considered preparatory to continue contributing to the criminal act, bypassing the preparatory phase, and causing the most possible harm to society and the state, with the punishment the same in all cases, without regard to the principle of grading punishments according to the seriousness of the acts. Modern legislation further considers mitigation over the principle of gradualism and guaranteeing amnesty for those who quit the criminal act or cooperate with the judicial authorities to prevent the implementation of criminal acts.

Article 207 stipulates the death penalty for anyone who promotes in the country, in any way, theories or principles aimed at changing the basic principles of the Constitution or the basic systems of the social body, or to overthrow the state’s political, social, and economic systems, or demolish any of the basic systems of the social body, using violence, terrorism, or any other illegitimate means. Anyone who possesses books, publications, drawings, slogans, or any other items with the intention of favoring the aforementioned acts, or favoring them in any other way, shall be punished with life imprisonment. Anyone who receives or obtains directly or through mediation, money or benefits of any kind from any person or any entity inside or outside the country for the purpose of promoting the aforementioned acts in this article shall also be punished with life imprisonment.

Article 208 stipulates “Anyone who creates, establishes, organizes, or manages in the country, without a license from the government or with a license issued based on false or incomplete data, associations, bodies, or systems of an international, non-political character, or a branch thereof, shall be punished with imprisonment. Any person involved shall be punished with imprisonment for a period not exceeding more than three months, and with a fine not exceeding two hundred dinars for any person who joins the aforementioned associations, bodies, or systems, as well as any Libyan residing in the country who joins or participates in any way without a license from the government in any of the aforementioned systems and whose headquarters are abroad.”

These articles cannot remain because of their contradiction with the Constitution and ratified international agreements, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and for the violations that may result from their continued adoption, including violation of the principles of fair trial stipulated in Article 31 of the Constitution, or violation of the right to freedom of opinion, expression, press, printing, publishing, and peaceful demonstration, according to Article 14 of the Constitutional Declaration, and the right to freedom of formation of parties and associations according to Article 15 of the Constitutional Declaration. The articles further violate the principles of state democracy enshrined in Articles 1, 4, and 7 of the Declaration and the right to life, which requires the death penalty to be considered an exceptional punishment for the most serious crimes. An Article of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights considered those articles from immemorial time and had no place in respecting the principle of the supremacy of the constitutional rule and what was stated in Article 35 of the Declaration regarding the annulment of contradicting legal texts.

The reference to international agreements ratified by the Libyan state, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights or the African Charter on Human Rights, is not a matter of legal grandeur or citing comparative law or international law to inspire general principles. These international agreements, once ratified, became legal texts of the Libyan legal system and bind the state with its legislative, executive, or judicial authorities. Numerous rulings have been issued that explicitly acknowledge the superiority of ratified international agreements over ordinary legislation, consistent with the explicit nature of Article 7 of the Constitutional Declaration of 2011 in regard to human rights, and with the obligations of the Libyan state included in each of those international agreements, and with the general rule in the article on international agreements contained in the Vienna Convention. The Vienna Convention considered the general text regulating international agreements, by ignoring the local legislative or executive authorities, and sometimes even the judiciary, which does not in any way weaken the superiority of international agreements over ordinary legislation and is guaranteed by the constitutional rules and explains the position of the Supreme Court when considering appeals of unconstitutionality and reminding it of the necessity of respecting those agreements.

Among the obligatory manifestations of the legal rule is the penal aspect, where the legal rule is a regulation of the behavior of individuals and groups in accordance with public order in various concepts and the protection of society. The legislator further resorts to ensuring that these concepts are not violated by criminalizing the violation and stipulating a punishment for it according to the gravity of the harm prevented and the danger to society and individuals, which is the field of criminal law.

Criminalization and punishment are affected by societal rules of behavior and their accepted value system, and the nature of the existing constitutional and political system in every country and in every era of time. In the 20th century, positive law appeared in the Arab countries with the emergence of the modern state, known as the national state in general. Most of these countries were not democratic states and lacked the principles of the state of law and institutions, leading to the use of positive law, including penal law, only favoring the ruling regime, and not the state or society. The penal law has come to protect the existing system of government, its founding ideology, and promotional or reference culture. Therefore, these laws did not respect human rights, but rather were a factor in perpetuating their violation and guaranteeing impunity, restricting any possibility of peaceful transfer of power, undermining constitutions and the sovereignty of the people.

During the monarchy or with the Jamahiriya regime, the Libyan state did not deviate from this ideology, accumulated with violations and defects, which led to the emergence of a revolution of the Libyan people who yearned for reform and the establishment of a state of law and democratic institutions. Despite the difficulty of the endeavor and the exacerbation of security and political problems, the Constitutional Declaration of 2011 was issued, declaring the birth of the Libyan revolution and confirming the revolutionary project to establish a Libyan state that respects human rights and cut ties with any legal legacy in which the executive authority and those in charge dominated the entire political, legal, and human rights scene.

The Constitutional Declaration of 2011 further reached the declaratory impact in its preamble, to explicitly adopt the democratic approach and respect for human rights as a first step, before adopting a permanent constitution for the country that crystallizes a qualitative shift in the structure of powers and their dynamics, to establish the sovereignty of the people and respect for their rights. Rather, the constitutional declaration became conclusive in its final provisions on opposing laws, stipulating that these laws must cease implementation, and the legislative authority must take the necessary measures to harmonize the texts with the constitutional rules.

The legislative authority harmoniously followed the Constitutional Declaration, and issued the Transitional Justice Law, declaring the invalidity of texts violating human rights, and issued the Political Parties Law, adopting the principle of declaration and not authorization, in establishing parties. However, the legislative effort was inconsistent and incomprehensive, and in contrary, governments, administrations, Public Prosecution, and the courts of origin attempted to revive legal texts with no relation to the Constitutional Declaration and the desired state of law. The legal heritage and laws of the dictatorship regime were enacted to suppress human rights and perpetuate the dominance of the oppressive regime. This behavioral phenomenon reflects a serious decline in the will to reform and the political will to respect the supremacy of the constitution.