The Scale of the Constitution: Obstructing the Constitutional Circuit and the Right to Access Justice

Libya’s Constitutional Declaration guarantees the right of every person to sue, by stipulating in Article 33: “Litigation is a right, safeguarded and guaranteed for all people (…).” Article 33 was included in Chapter IV, Judicial Guarantees. Although there are only three articles in the chapter, it represents an important pillar of the rule of law, wherein there exists the principle of an independent and impartial judiciary.

Judicial independence, as sought by the drafters of the Constitutional Declaration, does not end at “institutional independence,” meaning that the concept of judicial independence is not limited to the judiciary as an institutional authority in relation to the legislative and executive authorities, each operating according to their delegated functions. Rather, the concept of judicial independence, as envisioned by the constitutional drafters, extends to the judge when issuing a verdict or a ruling. This is stated in Article 32: “The judiciary is independent and run by courts(…), and judges are independent, and there is no authority over them in their judgments other than the law and conscience (…).”

Institutional or organic independence may be unachievable unless what the drafters of the constitution termed “judicial guarantees,” are sanctioned, or, in our estimation, unless fair trial or due process standards are guaranteed in general. Articles 31, 32, and 33 also affirmed:

1. The principle of legality: “There is neither crime nor punishment except on the basis of a text. The accused is innocent until proven guilty in a fair trial.”

2.” The defendant’s right to a defense is guaranteed.” The text of this article is insufficient because this guarantee does not apply to every trial, as it does not apply to punitive or disciplinary trials.

This Constitutional Declaration article text is insufficient because any trial requires such a guarantee, unless it is a punitive trial.

3. The right of every citizen to resort to justice in accordance with the law. This text is also insufficient because the right to access justice is the right of every person, not only citizens, as stated by Article 10 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Article 33 attempted to circumvent dedicating this right to all people by specifying it for citizens “(..) and every citizen has the right to resort to his natural judge (..)”

4. The principle of legality through the prohibition of exceptional courts (Article 23-2), and the prohibition of immunizing decisions from judicial oversight (Article 33-2).

5. The principle of invoking the natural judge (or non-exceptional judge), which is significant in Libya given the experience of exceptional courts following the 1969 coup.

6. The principle of bringing justice closer to its seekers and quick adjudication of cases (Article 33-1). Justice is not limited to simply approving the principle of justice in the governing Constitutional Declaration, but it further requires the state’s commitment to safeguarding human rights and freedoms in accordance with international declarations and covenants. This is affirmed in Article 7 of the Constitutional Declaration, which is in line with the general objectives expressed in the declaration’s preamble: “Achieving democracy, pluralism, and a state of institutions and a society of citizenship and justice (..), in which there is no place for injustice, despotism and tyranny (..).”

Although the Constitutional Declaration refers to the judiciary without any description, it is recognized in the field of interpretation to be absolute, which means that the legislator has preserved the judicial structure with the exception of what is exceptional. This analysis is confirmed by Article 35, “All provisions established in existing legislation shall continue to operate, provided they do not conflict with the provisions of this declaration, unless amended or abolished (..).”

The judicial system in place at the time of the Constitutional Declaration remains concerned with granting every person the right to resort to the courts, including the Supreme Court (Article 20 of the Judicial System Law no. 6 of 2006). The Supreme Court’s jurisdiction is specialized to rule on constitutional appeals, which inevitably ensures the right to access justice by guaranteeing the mechanism for addressing constitutional violations, as regulated by law. This means the amended Law no. 6 of 1982 remains in effect, about the organization of the Supreme Court, which grants the right to constitutional challenge, in addition to appealing cassation rulings issued by lower courts.

However, the Constitutional Circuit assigned by the legislator to consider constitutional issues was suspended according to the General Assembly of the Supreme Court’s issuance of decree no. 7 of 2016, regarding the suspension of the Constitutional Circuit’s activities. The decree stated, “Rulings on constitutional appeals are postponed to a date to be later determined by a decision of the General Assembly.” This suspension is similar to another precedent under the previous Gaddafi regime, which came after the restoration of the Constitutional Circuit that had been abolished by the legislature in 1982. The General Assembly had been reluctant to issue the internal regulations referred to by Law no. 17 of 1994 in amending Law no. 6 and to reinstate the Constitutional Circuit with regard to constitutional appeals procedures.

So it is as if history repeats itself, thus raising a dilemma of distinguishing between the two previous constitutional circuits (to be discussed in Section I), before inquiring about the legitimacy and legality of the General Assembly’s decision to suspend the aforementioned circuit (to be discussed in Section II), and what are the implications on the rights of litigants (to be discussed in Section III).

Section I: Suspension of the Constitutional Circuit, despite different governing administrations

The suspension of the Constitutional Circuit’s activities may not differ from its dissolution, which covered the period between the enforcement of Law no. 6 of 1982 (which implicitly abolished the circuit) and the enforcement of Law no. 17-94 amending it (first point below). Nevertheless, the most important aspect to note is that the mechanism may differ (second point below).

First: The difference in the mechanism suspending the work of the circuit

The conduct of the General Assembly of the Supreme Court may differ in comparison to the legislature’s conduct in regards to the existence of the Constitutional Circuit. In 1982, the General Assembly of the Supreme Court used its sovereignty privilege and abolished the Constitutional Circuit’s control over the constitutionality of laws, as had been entrusted to it. The Constitutional Circuit was viewed as standing in the way of ‘reforms’ that the General Assembly sought to implement. These reforms affected a number of rights, the most important of which are the right to be free and the right to own property, according to the ideology espoused at the time by Gaddafi’s literature.

The first precedent of the General Assembly was established during the period of 1993 to 2004. During this time, the General Assembly would agree with the “leader” or out of piety and take a negative stand against the Constitutional Circuit by refraining from issuing the internal regulations on which the circuit’s work depends. Then after over a decade of absence, the Constitutional Circuit was brought back to life by the General Assembly’s issuance of a resolution approving the internal regulations. (The General Assembly of the Supreme Court Resolution in session no. 283 of 2004).

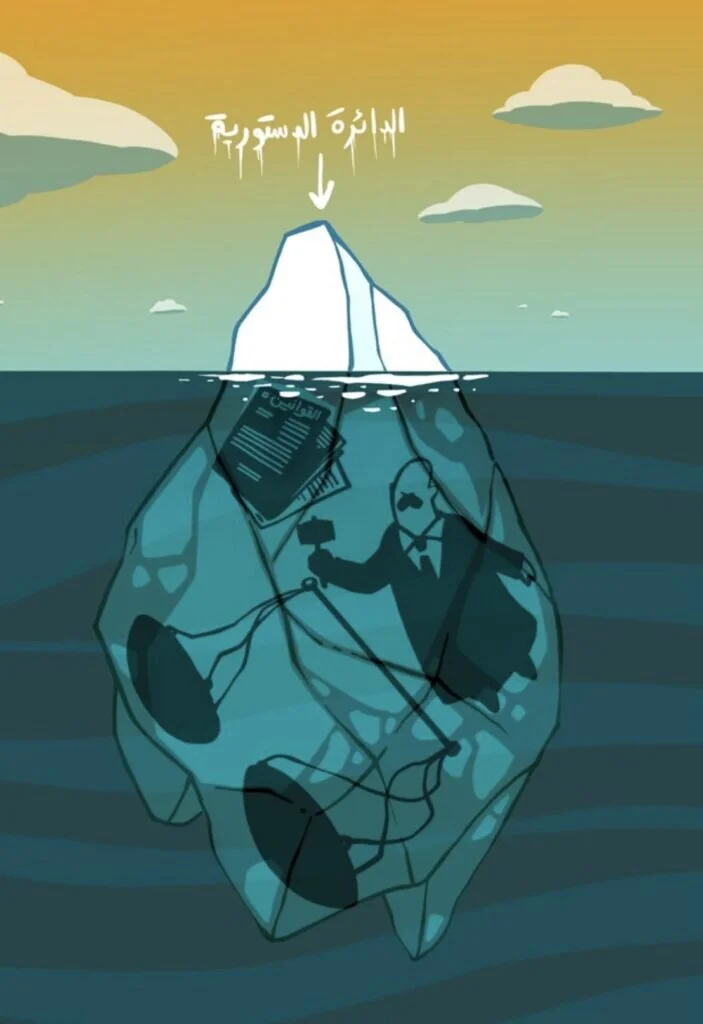

In 2016, the General Assembly directly suspended the work of the Constitutional Circuit by issuing Resolution no. 7 of 2016, which froze and suspended the circuit’s activities, without abolishing it. Although the circuit still exists with its activities suspended, it is dormant and without life. Yet people who are not legal professionals may be deceived into thinking that there must be constitutional oversight by consequence of the Constitutional Circuit’s existence, without realizing the extent of the circuit’s dormancy.

The misconception of constitutional oversight is perhaps further bolstered by the Supreme Court’s continued acceptance of constitutional appeals administratively in accordance with prescribed regulations. The constitutional appeals process is regulated through an application in its original form and sufficient number of copies that is signed and filed by a lawyer who is competent to plead before the Supreme Court. The complaint or application is then handed to the competent registrar of the Supreme Court (Articles 12 and 13 of the bylaws). Needless to say, this process remains only a mechanism without any activity, as the final decision is relegated to the authority of the court – in regards to whether or not the appeal file is referred to the Cassation Prosecution to express its opinion within a specific period, following the announcement of defendants and after submitting the necessary documents in Article 15 of the bylaws.

The head of the Supreme Court is the one who refers the case file to a member of the assembled circuits that deal with constitutional appeals, to develop a report summarizing the facts and legal issues in place of dispute. After the appeal has been reviewed, the assigned advisory member deposits the file to Specialized Registry. The case file is returned again to the head of the Supreme Court to assign a session (Articles 16 and 17 of the bylaws). This indicates that any appeal is subject to the will of the head of the Supreme Court, which is confirmed by comparing the results of the suspended appeals with the appeals that were accepted but remain inactive, with no further processing.

Second: Dissolution and freezing, two sides of one coin

Observers of the dissolution, suspension, and/or freezing of the Constitutional Circuit find that despite the variety of means channelled towards achieving the intended purpose, the result is effectively the same: a lack of oversight on the constitutionality of laws. This can be confirmed by the immediate appeal of a case affecting rights and freedoms, after the issuance of the law to reorganize the Supreme Court (Law no. 6 of 1982); a punitive text was applied before the law was published. The Supreme Court’s response was shocking, when it ruled that it had no jurisdiction to monitor the constitutionality of laws. Jurisprudence experts viewed this as the court abdicating from its responsibility to monitor constitutionality. Even though the legislator abolished oversight control over legislation, in which written authorization is required, the judiciary is not prevented from exercising oversight abstention.

Citizens found themselves in a similar situation when the legislator returned jurisdiction to the Supreme Court to monitor constitutionality of laws but the General Assembly did not amend its bylaws to specify the procedures for filing constitutional appeals. The situation remained as it was for nearly a decade until the bylaws and regulations were issued in 2004.

Following the decision to suspend the work of the Constitutional Circuit in 2016, Libya returned to a similar situation: ineffective oversight of the constitutionality of laws despite such oversight being enshrined legally. This indicates that the effectiveness of laws is not reliant upon the texts contained in the laws themselves, published in the Official Gazette, but it is also – and moreover – contingent upon on the how laws are applied and fulfilled. This can be further illustrated by the General Assembly’s issuance of Resolution no. 7 of 2016, in regards to which people were prohibited from exercising their right to challenge the resolution’s unconstitutionality, even though such a challenge is theoretically possible, according to legal text. This prompted some people to use the appeal mechanism of the administrative authority to compel the General Assembly to change its position. Others submitted an appeal to the Tripoli Court of Appeal to repeal the resolution of the General Assembly of the Supreme Court. The third administrative circuit issued a verdict to annul the resolution on 24 February 2020, after nearly four years (unpublished verdict).

However, revoking or withdrawing decisions of the General Assembly may not be the end of the suspension/freezing pattern of oversight on the constitutionality of laws at the practical level, because the head of the Supreme Court, as mentioned above, has other means to delay the return to work of the Constitutional Circuit without fearing the obstruction of justice that founded the litigation case.

It is clear that the difference between abolishing and freezing the work of the Constitutional Circuit is merely a difference in degree. In practice, the results are almost identical, similar to two sides of the same coin. What matters to those seeking justice is accessible justice and the protection of their rights or legal positions. And in their defense, they could resort to using oversight of the constitutionality of laws, whether in the form of a plea or a lawsuit filed directly to the Constitutional Circuit (Article 23 of Law no. 6-82 on the reorganization of the Supreme Court).

Section II: The legitimacy and legality of the General Assembly freezing the Constitutional Circuit

At the outset, it is necessary to mention a cursory reference to (legality – legalité) and (legitimacy – legitimité), meaning in my opinion, that what is approved by law is legitimate, regardless of whether or not it conforms to what is required, because the condition of the latter is legitimacy. A question thus arises: To what extent does the decision to freeze the Constitutional Circuit’s activities correspond with the law regulating the Supreme Court, and if it corresponds, is it legitimate from the perspective of justice or human rights?

First: Alleged legality

Supreme Court Law no. 6-82 sets forth the competencies of the General Assembly, which issued the decision to freeze the Constitutional Circuit. Following close inspection of the law, we find that Article 51 grants the General Assembly (which is composed of the head of the court, the court advisors and the head of the cassation prosecution) the authority to decide on “(..) issues related to its system, its internal affairs, the distribution of work among its members or between its departments, and other matters falling within its competence under this law or any other law (..).” The General Assembly has only been granted what the legislator drafted in the law organizing the court or any other law, which means that it does not have any authority outside its specific jurisdiction.

Article 51 of Law no. 6, in its fourth paragraph, further stipulates that the General Assembly is granted the authority to set its own bylaws list of procedures. Article 55 assigned the assembly the authority to “organize the court’s records and files, how documents are submitted to the court, the conditions for rebuttal, and how the litigants peruse the documents (..).” The assembly has the power to choose the counsellor of the disciplinary board for the court’s employees (Article 41), and has prescribed powers to the Ministry of Public Service for court employees (Article 35), which is the body before which the court’s counsellor takes oaths (Article 8). The Supreme Court holds its sessions outside the city of Tripoli by a decision of the General Assembly (Article 4). Law no. 33 of 2012, amending Law no. 6, adds a new jurisdiction over the extension of service of the president and counsellors of the Supreme Court, who have reached the retirement age (sixty-five years) to the age of seventy at the request of the concerned side. The General Assembly may also decide to release whomever it deems unable to perform their job for any reason, even without their consent (Article 14 amended).

This indicates that the legislator did not grant the General Assembly of the Supreme Court the power to suspend the work of the court or any of its circuits, which was confirmed by the Tripoli Court of Appeal in its ruling mentioned above. The court of appeal supported the arguments of the appellant in issuing a verdict. “(..) The right to resort to the judiciary is one of the basic rights that must not be deferred or obstructed, as stipulated in the Constitutional Declaration Article 33, as well as all international conventions (..).” The court added another argument, which is the Supreme Court itself has set the principle of resorting to the judiciary since 1957 on the occasion of administrative appeal no. 6-3, which required the administrative decision to be “in conformity with the constitution, laws, regulations and principles of public law, such as equality and public freedoms.” Other circuits in appeal no. 13 had the same argument, which considered the right to resort to the judiciary as a fundamental right.

The court supported the appellant’s argument that the General Assembly’s decision to suspend the work of the Constitutional Circuit contravenes the Constitutional Declaration, and lacks a sound purpose. The purpose of administrative decisions is to achieve the public interest; if an administrative decision serves another purpose, then it is flawed (..). Thus, the court concluded, “(..) Any delay in issuing a decision on constitutional appeals for the contested part of the decision of the General Assembly of the Supreme Court for an unknown period, disrupts the achievement of the public interest, and limits resorting to the judiciary in constitutional disputes that are predominant in the nature of public interest, especially amid Libya witnessing contradiction in the legislative bodies, the executive bodies, and the various administrative institutions (..).”

The court decided to annul the decision under appeal, not only on the basis of the validity of the appellant’s argument, but also because such cases against the respondent or defendant, who is the President of the Supreme Court, did not discuss the subject of the appeal; instead, they simply discussed the acceptance of the case. The court had rejected the case at an earlier stage, when discussing the request to halt the implementation of the decision. According to the court, the prosecution’s note did not reflect a consistent position; sometimes, the appeal is handled in terms of form and jurisdiction, and other times, the appeal is handled by an urgent verdict. The prosecution’s opinion was to reject the appeal on the grounds that the Supreme Court does not issue an administrative decision, but rather, it issues a judicial verdict, which is binding on lower courts. This is not a sound opinion. The court said, “The decisions of the Supreme Court, while exercising its administrative function through the General Assembly, are either organizational -related to the distribution and organization of work between its various departments- or they are administrative, in that they affect the legal status of others, so such decisions are subject to appeal by annulment (..).” The court concluded that the opinion of the Public Prosecution is invalid because the General Assembly’s decision was issued within its administrative capacity and outside the scope of judicial function, and therefore it is subject to appeal.

The verdict shows that the court did not specify the necessary justifications for challenging the appellants’ defense, nor did it justify reaching the verdict. Rather, the court attempts to convince the subsequent oversight court, if there is an appeal in cassation, that what the ruling has concluded is an application of the judiciary of the Supreme Court itself. The appeal court considered the verdict as “(..) A reminder of these rulings is only due to the high status and prestigious position of our esteemed court. Despite the political sensitivity of these provisions (..), my response to the appellant’s request to annul the General Assembly’s decision to suspend the Constitutional Circuit activities is only the fruit of the jurisprudence of the Supreme Court’s judiciary in constitutional disputes, which is one of the building blocks of political life over time.”

Accordingly, and since the legality is dependent on the existence of a text that justifies the procedure or decision, its absence, in the hypothesis in question, leads one to say that the decision to suspend the Constitutional Circuit’s activities is illegal.

Second: Lack of Legitimacy

Consequently, the suspension of the Constitutional Circuit is also illegitimate. Regardless the source of the illegitimacy (natural law, justice or human rights), the suspension created unjust conditions under which people could not object by filing a lawsuit or a plea for unconstitutionality. Do the circumstances of the transitional period justify such a decision? Who remembers the negative effects of the ruling issued by the Constitutional Circuit, concerning the election of the House of Representatives in 2014, in which it concluded that the Seventh Amendment of the Constitutional Declaration was unconstitutional; this ruling was the basis upon which the House of Representatives was elected.

Some may find justification for the General Assembly in fear of new divisions that could further rupture national unity. However, the manifestations and fluctuations of the transitional phase in Libya following the fall of the Gaddafi regime cannot destroy the basic principles upon which the legal system in Libya is based. These include the principle of separation of powers, which has become ambiguous since the Constitutional Declaration was issued in 2011; the principle of guaranteeing the right to litigation, and the principle of legitimacy. Perhaps the confirmation of such principles, particularly legitimacy, can be found in the following Supreme Court ruling, which stated:

“It is illegitimate for the legislative authority to issue a law or for the executive authority to issue a decree or a law that eliminates or diminishes the independence and immunities of judiciary members (…).” (Constitutional Appeal no. 1-14)

On another occasion, the Supreme Court as a constitutional court affirmed that stripping constitutional rights of the effective means to protect them – i.e. stripping a person of their right to resort to the judiciary to seek redress, would render the constitutional text related to these freedoms futile in practice. In other words, the constitutional text in practice becomes violated so long as the legislator can withhold the rights of judicial protection on the basis of the legislator’s right to regulate education or to regulate litigation. This is because the rights specifically stipulated in the Constitution must not be permitted to fall under the legislature’s authority, in regards to regulating such rights or confiscating them. (Constitutional Appeal 1-19).

If the legislator does indeed regulate or confiscate such constitutional rights, then the court’s General Assembly does not have any right to deprive constitutional rights of the organized means of protecting them, including the right to litigation, whether such litigation is related to challenging unconstitutionality or defending it. It is insufficient to say here that the aforementioned General Assembly simply stripped constitutional rights of their protective tool – the judiciary – but regardless, the General Assembly has completely suspended the role of constitutional rights during the transitional period in Libya, following the division resulting from the election of the Council Representatives.

An inherent established right cannot be restricted under the legislative authority of the General Assembly. The General Assembly’s authorities and responsibilities are organizational and specific. Moreover, the problem is not necessarily with the exercise of oversight, but with the ability of the judges of the Constitutional Circuit to handle appeals and reach solutions serving the principle of legality, the supremacy of the constitution, and the rule of law; while maintaining societal cohesion and preserving national unity. Finally, the General Assembly, with its current stance, violates Article 31 of the Supreme Court Law, which states that the principles of the Supreme Court are mandatory for the courts and for all institutions. It is thus flawed for the General Assembly to set any other precedent than good faith in upholding these principles and the institutions that fall under them, as the guardian of legality and the rule of law.

Section Three: Freezing and Litigants’ Rights

Regarding the organization of the work of the Supreme Court departments, including the Constitutional Circuit, we find that the amended Supreme Court Law no. 7 of 1994 singled out the Constitutional Circuit, which is exercised by combined circuits, to adjudicate appeals raised from anyone with a direct personal interest in any legislation that contravenes the constitution. The Constitutional Circuit considers any substantive legal issue related to the constitution or its interpretation raised in a case before the courts (Article 23, first and second); meaning that the suspension affected all functions of the Constitutional Circuit (first), and it is uncertain that the courts will compensate for the lost work of this circuit (second).

First: Freezing the Constitutional Circuit, the Right of Appeal, and Unconstitutionality

Since 1953, the system of oversight on the constitutionality of laws in Libya is distinguished by its dedication to the right of anyone who is harmed, directly or indirectly, by the violation of the constitution by legislation. A harmed person thus has the right to challenge or argue the legislation’s unconstitutionality, and prevent its implementation. According to the Supreme Court, “This right is established without waiting for any legislation to actually be implemented (..)” (Constitutional Appeal no. 3-6). Freezing the work of the Constitutional Circuit, on a practical level, entails:

1. Depriving people of their right to directly challenge legislation that does not adhere to the Constitutional Declaration, which is the current source of legality or legitimacy according to the Supreme Court. Although citizens are able to initiate the right to appeal in accordance with established procedures, the appeal will remain frozen, thus leading to an accumulation of appeals, and further deferring justice in a judicial system that already suffers from slow due process procedures. In principle, the implementation of laws depends on simple publication in the Official Gazette. After publication, the laws are then applied even if flawed or tainted with unconstitutionality, as the original drafted laws are deemed valid until the Constitutional Circuit rules on their unconstitutionality.

2. The matter does not end with the right to file a lawsuit; the freezing also, in practice, infringes upon the right to plea. Litigants can find themselves exposed to the application of legislation (laws or regulations), and can raise this or plea before the trial court, but to what end or for what result? The case will remain suspended. Even if the court adopts the plea, it will not be able to proceed with it, as long as there is no solution from the suspended Constitutional Circuit. Litigants thus faces a contradictory situation in regards to the law and justice, while being stripped of the means to protect their rights. What does a right without protection mean? This negative conclusion does not necessarily reflect reality, because the courts, in the exercise of their function, can compensate for the imbalance.

Second: Courts and reducing the effects of freezing

Freezing the Constitutional Circuit has undesirable consequences upon the rights of litigants. As mentioned above in the previous paragraph, this situation raises the question: to what extent can these consequences be remedied by referring the litigant to lower courts to request a ruling in regards to the application of any legislation or legal text that contradicts or violates the implemented constitutional rules? The reorganization of the Supreme Court in 1982 by Law no. 6 and the abandonment of constitutional oversight by the Supreme Court was met with criticism due to the absence of a text granting jurisdiction, rendering it impossible to apply texts that conflict with the constitution or its equivalent in application of the principle of gradation in legislation.

A judge’s duty is inclined towards verification of the veracity or legitimacy of the applicable rules. When a judge excludes violating rules, it is not considered a violation of the principle of separation of powers, as oversight here is akin to the oversight abstention, which does not require the presence of a published law or bylaw. Given that the Supreme Court has exclusive jurisdiction over the Constitutional Circuit, is it possible for a judge to fulfill their obligation of exercising oversight in the current reality wherein the Constitutional Circuit is ineffective due to its illegal and illegitimate suspension by the General Assembly the Supreme Court?

The answer is no, it is not possible, because the circumstances are not the same. The legislator today is not against oversight, the opposition instead comes from the judges charged with guarding legitimacy and proper implementation of the law. The law organized the means of changing the judge’s stance regarding oversight. These means are the litigation procedures regulated by the pleadings law: wherein the judge can be opposed in specific circumstances stipulated exclusively in Article 720, including the circumstances of denial or delay of justice without justification.

The freezing carried out by the General Assembly constitutes a justification that does not prevent litigation of the assembled departments concerned with examining appeals and constitutional issues. This statement was rejected, because the principle of gradation of legislation and ensuring the right to litigation is a priority. Perhaps what confirms the effectiveness of this method lies in the history of constitutional oversight in Libya, with resorting to the threat of litigation. After the restoration of jurisdiction over constitutional oversight of the Supreme Court by Law no. 17 of 1994, and the reluctance of the General Assembly to issue its internal regulations or bylaws, some lawyers threatened the head of the court with resorting to litigation if the regulations were not issued, which occurred in 2004.

Another lawyer resorted to another method, which was to challenge the freezing decision before the administrative judiciary. The Administrative Judiciary Circuit of the Tripoli Court of Appeals responded to the request, and annulled the relevant decision. This is a natural course, because Administrative Judiciary Law no. 88 of 1971 permitted the appeal before the administrative judiciary circuits of the courts of appeal in the final administrative decisions (Article 2); where the basis for the appeal is lack of jurisdiction, defect in form, violation of laws and regulations, error in implementation or interpretation, or abuse of power. This procedure is quite protracted because the ruling of the circuits is not final. However, it is permissible to challenge it by cassation before the Administrative Circuit of the Supreme Court, although with the time that this requires and the possibility of the ruling being overturned, we are thus brought back to square one.

Litigation is the first procedure, the most appropriate and shortest, perhaps given that the case is filed directly before the Supreme Court. Nevertheless, litigation in this context is not a complete either. The jurisdiction, after the verdict the of the competent circuit of litigation is issued, is vested in the assembled circuits of the Supreme Court (Article 725 pleadings).

However, excluding the participation of the subject courts in compensating the role of the Constitutional Circuit does not entail diminishing its other role in the oversight of legality outside issues of a constitutional nature. This was also exploited by those with conflicting interests, especially the temporary judiciary, which is the system of orders on petitions and urgent cases. Thus the overall complexity of the scene was further exacerbated alongside further division or fragmentation of various institutions.

Several justifications were given to the position of the Supreme Court, including the difficulty of fulfilling the task of constitutional oversight amid political division, the lack of security, and the proliferation of weapons that were used to storm the Supreme Court after the election of the House of Representatives. These justifications led to the suspension of the Constitutional Circuit. Nevertheless, that did not prevent the lower courts from considering numerous petitions and lawsuits related to the transitional path or its events, including sovereign positions, referral of the draft constitution, elections, and so on. Judge Khalifa Ashour explained and referred to this in his doctoral thesis, which considered that reliance upon the Supreme Court – with its old structure- to bear the burden of constitutional oversight during the transitional period (and without detracting from its prestige or highness and integrity of its advisors) is the main reason for the Supreme Court’s suspension of the Constitutional Circuit.”

The task of oversight – disrupted by the freezing of the Constitutional Circuit – obstructed the various fields of litigation without discrimination, the decision stated, “Appeal or plea in legislation is contrary to the Constitution (Article 23 of Law no. 6).” This deprives litigants of a fundamental means of defense, which turns the case in favor of those supporting the freezing of the constitutional circuit.

As a conclusion:

The decision of the General Assembly of the Supreme Court to suspend the work of the Constitutional Circuit came as a result of the regressive waves caused by the circuit’s ruling in Appeal Case no. 17 of 61 on the procedures for the election of the House of Representatives in 2014. The Supreme Court cultivated the outcome of this decision by meddling in the political conflict, which caused the majority of the people to question its rulings and provisions, and its prestige. Perhaps the lesson learned is that the judiciary must maintain its independence, and be keen on distancing itself from areas of political conflict by adhering to the values of impartiality, integrity, and the rule of law. As for choosing the easiest path, which is to disable the institution or some of its components, this would deprive people of a basic right guaranteed by the constitution, the right to access justice. The right to access justice is the sturdy bridge linking together the protection of rights and freedoms, and is a fundamental pillar of the rule of law. The judge, according to Ibn Ashour, is required to have “authenticity of opinion and knowledge, safety from the influence of others over them, and justice.”

To this day- after the verdict issued by Tripoli Appeals Court to annul the decision suspending the Constitutional Circuit, and after the General Assembly of the Supreme Court’s decision to activate the work of the circuit – the issue remains unresolved. The Cases Administration of the Supreme Court did not accept the aforementioned verdict, so it appealed in cassation (Appeal no. 68-69). The appeal was based on the following: The Tripoli Appeals Court is not specialized to look into the case, and the General Assembly’s decision is a judicial decision issued by the Supreme Court rather than an administrative one.

The issue remains regarding the integrity of the establishment of the Constitutional Circuit. The Administrative Circuit of the Supreme Court, if given the opportunity to review the aforementioned case after a referral by the President of the Supreme Court, can process the right of appeal for constitutional oversight by accepting the appeal and reversing the judgment. Thus addressing the issue of oversight cannot be primarily contingent upon the text of regulations, provisions of law, or articles of the constitution. Rather, oversight must be based upon respect by both the governing and governed, whether those being addressed or those applying; and it is this respect that represents the essence of the rule of law.